THE VERTICAL URBAN FACTORY: A REVIEW

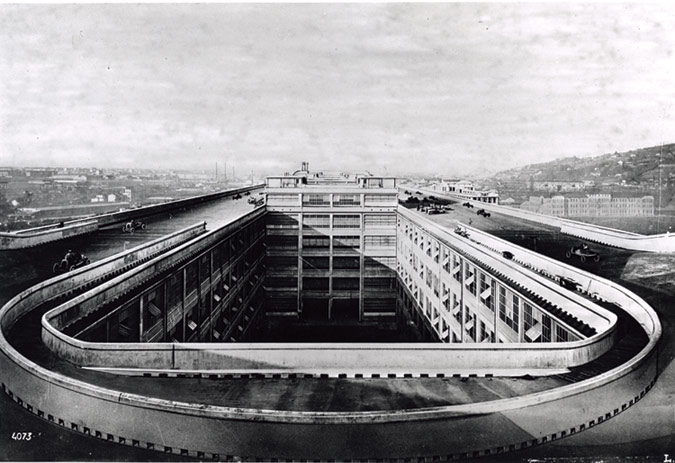

The famous race track atop the Lingotto Fiat Factory (1923) in Turin, Italy. Dylan Lathrop / Courtesy MOCAD

The Vertical Urban Factory. Currently on display at Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, The Vertical Urban Factory is an independent research project and exhibition curated by architectural historian and critic Nina Rappaport. This traveling display explores historic and modern concepts for the design, structure, mechanization, and socioeconomics of multi-storied factories that are both urban—integrated into cities—and vertical—integrated floor by floor according to programmed manufacturing processes. Divided into three separate zones, the exhibition investigates significant architectural precedents, both built and unbuilt; makes a geo-spatial comparison between Detroit and New York’s (post) industrial inventory; and displays alternative contemporary models that demonstrate the potential environmental, social, and economic benefits from the reintegration of well-programmed vertical factories. Rappaport further suggests that industrialists and urban planners should reconsider the potential for building vertically in cities: “This, in turn, would reinforce and reinvest in the cycles of making, consuming, and recycling as a part of a natural feedback loop in a new sustainable urban spatial paradigm.”

Rappaport’s paradigm combines the desired altruistic 21st century industrial traits: clean, green, light, networked industry spatialized within different vertical, sustainable forms. The thesis is clear, the research is powerful, and the selected contemporary projects are beautiful, suggesting a myriad of innovative architectural approaches to the vertical manufacturing process. However, one must still question whether verticality is an appropriate industrial paradigm for all urban fabrics.

The spatial and economic factors that would ordinarily force urban manufacturing into a vertical arrangement are less evident in Detroit than in other industrial cities. In the post-war military-industrial era, the very same leaders of industry that invented vertical production strategically shifted their spatial focus towards sprawling, decentralized, horizontal factories far from the urban core. The vast stretches of Detroit’s under-utilized or abandoned post-industrial urban fabric thus stand in stark contrast to the constraints of industrial Manhattan or Hong Kong. As evidenced by the side-by-side mapping of Detroit and New York City, Rappaport’s paradigm really only addresses a solution appropriate to a dense urban setting and seems absurdly irrelevant when applied to many post-industrial urban areas found in the ‘Rust Belt.’ In Detroit, a city overwhelmed by 40 square miles of vacant land, why rely on verticality as the primary model? What is the post-industrial version of the vertical urban factory?

There is another way: the modern post-industrial urban factory should be neither vertical nor horizontal, nor does it have to be confined to a single building or campus. Offering greater benefit, this (un)vertical urban factory would be a multi-scalar matrix that weaves architecturally, spatially, economically, and socially throughout the city, linking production facilities to neighborhood amenities. Pulling attributes from social-networking and new communication media, the post-industrial paradigm could be an urban design constellation of interdisciplinary facilities, linking design, supply chain, production, and consumers to the urban context, while providing opportunities for cultural and civic interaction. The (un)vertical urban factory would defray short-term profit in favor of long-term investment in the physical and social infrastructure of the city and region, leading to long-term economic health.

In the post-industrial city, the emerging model of the factory is no longer solely reliant on architectural innovation as it was when Albert Kahn was integrating new materials and methods in the early part of the 20th century or as illustrated by the beautifully engineered architectural precedents displayed in the exhibition. The new challenge is about creatively redefining the very need for an urban factory.

The famous race track atop the Lingotto Fiat Factory (1923) in Turin, Italy. Image courtesy of Dylan Lathrop / MOCAD.