reFACING DETROIT : A HOUSING NARRATIVE : PART 1

HOUSE NO. 1. I step out of my car and glance at the address listed on my clip board. I then compare that number to the faded house number adjacent to the front door. It’s a match. My partner and I glance at the neighborhood and quickly assess our surroundings. We traverse the short front walk, step up the slightly deteriorating stoop, and ring the doorbell. It doesn’t work. I tap my clipboard hard against the locked storm door. I stand square with the front door, my Detroit Housing Commission badge daggling from my shirt pocket. Like standing before a metal detector at the airport, I allow a stranger to scrutinize my intensions. I give ample time for them to complete their security check through the peephole. As I stand there, my mind wanders. What will I find on the other side of the door?

REHABILITATING DETROIT. In 2009, the federal government passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. It was enacted as an economic stimulus package and immediately pumped $12.7 billion towards the modernization of the nation’s public housing. New leadership at the Detroit Housing Commission (DHC) has earmarked $8 million toward breathing new life into a scattered sites housing program that has proven national success. Through this capital outlay, the DHC is continuing its mission to provide quality housing for all Detroiters. Hamilton Anderson Associates is one of four teams of architects asked to take this journey of rehabilitation with the DHC. Our specific task is to assess the physical condition of 80 homes, but as our work continues, we realize our assessments are also about restoring the human condition.

HOUSE NO. 14. The door opens and I walk in. Countless clipboards have already ‘surveyed’ their living conditions only to leave and never to be seen again. A woman in a hospital bed lies on her back, head propped up by a pillow so that she can listen and watch the small television on the opposite side of the room. The gurney is squeezed in amongst living room furniture. Her eyes follow me as I survey the room.

THE DETROIT HOUSING COMMISSION. Seventy-five years ago, the Detroit Housing Commission was created “to provide safe, decent, and affordable housing for the citizens of the City of Detroit.” With First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt helping to break ground, the DHC constructed two housing sites—Sojourner Truth for whites and Brewster-Douglass for African-Americans. The later became the nation’s first federally funded public housing development for African-Americans. These early developments were meant to “reward the worthiest among the temporarily poor…those who passed muster as good citizens and good investments.”

In an attempt to alleviate issues of extreme poverty, crime and segregation at many of its urban developments, many public housing authorities (including DHC) developed the scattered-site housing concept. In 2009, this translates to DHC’s ownership of over 370 single-family homes scattered throughout the City. Placing its property management issues in the past, Hamilton Anderson (HAA) is proud to stand with the DHC as it uses its scattered sites program to reintegrate families into communities, to stabilize disinvested neighborhoods and to create new opportunities for its tenants to own a home.

HOUSE NO. 22. It’s 10am. A slender woman answers the door. She apologizes for the beer in hand and turns off a loud playing stereo. The noise level barely lowers; the television is also on. As we talk, she blurts out how I’m a good looking man. I quickly realize the loneliness that screams just as loud as the television’s distracting din. Midway through the survey, she stops to ask me if it’s normal for houses to make noise. “Have you ever heard footsteps in a hallway when no one is there?”

DETROIT’S HOUSING CRISIS. Detroit’s housing stock is growing increasingly old. Based on 2000 Census data, 51.5% was built between 1940 and 1959; 29.9% was built before 1939. Despite these statistics, housing demands continue to grow. HUD estimates about 23,000 households in Detroit are on the waiting list for federal housing assistance. In 2001, HUD reported 51,000 low-income renters in the city of Detroit (with incomes less than 50 percent of the area median) paid more than half their income for rent, or lived in severely substandard housing. The Coalition on Temporary Shelter

(COTS) estimates Detroit’s homeless population at 9,500. Of those that find shelter among Detroit’s 1,995 emergency shelter beds, 23% are children.

HOUSE NO. 57. We return to a house to find the police and a DHC representative speaking to two adults. The squatters are being told they have 24 hours to remove their belongings. Once inside, we find the home fully furnished. We find breakfast still sitting on the stove. We notice two children bedrooms. The children will be returning from school to find that they have no longer have a home.

ARCHITECT’S HAVE A RESPONSIBILITY. We’ve all seen pictures, like those at Sweet Juniper! or The Fabulous Ruins of Detroit. Recent Time Magazine images depict a city of static, abandoned objects, devoid of life. These images fail to capture the human condition as found in the photography of Gordon Parks and Dorothea Lange or local photographers Romain Blanquart and Brian Widdis. As we step inside these homes, we realize that the outside world is holding a funeral for a patient that has not died.

We’ve spent the last five months immersed in Detroit’s neighborhoods and can confirm that it is very much alive. In the most distressed communities, we’ve found those that try to find dignity in their living conditions and those who have completely relinquished control of their living environments. In either case, these people demand our attention.

Architects are licensed to protect the health, safety, and welfare of the people, but what’s missing from today’s signature architecture is an infusion of social responsibility. Architect’s must recognize that’s it’s not enough to build for oneself, but one must build for a community. Hamilton Anderson Associates is helping the DHC not just renovate its house stock, but create places for families to live.

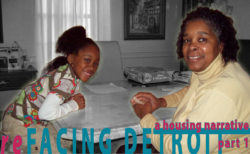

HOUSE NO. 62. As I move back downstairs, I hear a young girl reading to her mother. The young girl sounds her way through words, occasionally leaning on her mother when the words are unfamiliar. I’m reminded of my own seven year old daughter reading to my wife. The two are laughing. As I begin to leave, the mother stops me to ask how, despite losing her job, can she be placed in a homeownership program. Having paid rent for more than 20 years, she’d like to own her home. I tell her DHC will get back to her and wonder if there is anything I can do to make her wish come true.

DETROIT’S FUTURE. As of today, we have surveyed over 80 houses and spoken to hundreds of people. In future entries, we will convey stories that have happy endings. Detroit is more than ruins, it’s a city filled with people trying to find dignity amidst a sometimes unsympathetic world. By giving a person quality housing, we are not only investing in the stabilization of neighborhoods, but also in the ability to lift themselves out of poverty. Instead of focusing on pictures of abandoned buildings, we will give voice to people who are part of our community. By placing their stories within this context and physically improving their quality of life, we improve the quality of life for everyone.