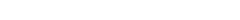

A BRIEF HISTORY OF DETROIT’S BLACK BOTTOM NEIGHBORHOOD

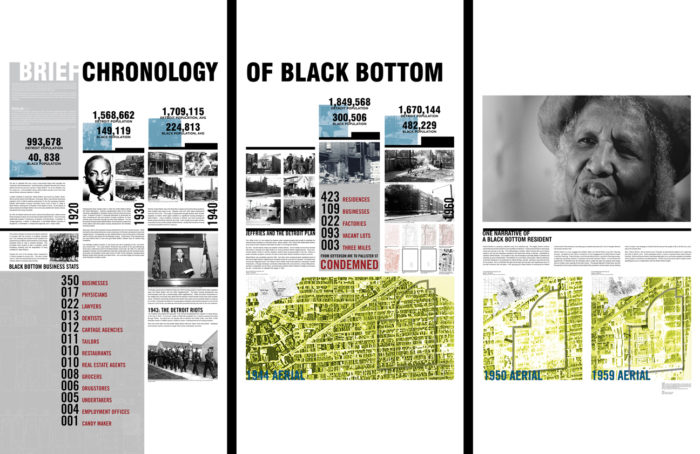

As co-curator of the INSIDE LAFAYETTE PARK exhibition, rogueHAA designed an installation and timeline highlighting the contrast of current life in the urban renewal development both to its architecture and its contentious past. The timeline, BRIEF CHRONOLOGY OF BLACK BOTTOM, also featured the “Detroit Stories” video interview with Bernice Jamerson, a former Black Bottom resident.

1920s. The site of Lafayette Park has a long, controversial history that precedes the modernist urban development. Centuries before Lafayette Park was built, French settlers farmed the area and named it “Black Bottom” for its dark, fertile soil and low elevation. In the twentieth century, Black Bottom became one of the most vibrant African American districts in Detroit.

Located northeast of downtown, Black Bottom was bound by Gratiot, Brush, Vernor and the Grand Trunk Railroad. In the early 1900s, many African Americans migrated north to Detroit seeking employment in the city’s growing industries. Racially discriminative housing covenants forced most of them to settle in Black Bottom, altering the connotation of the district’s name. As thousands of blacks streamed into Black Bottom, the community swelled with vibrant cultural, educational and social amenities.

The district reached its social, cultural and political peak in 1920. Blacks owned 350 businesses in Detroit, most within Black Bottom. The community additionally boasted 17 physicians, 22 lawyers, 22 barbershops, 13 dentists, 12 cartage agencies, 11 tailors, 10 restaurants, 10 real estate dealers, 8 grocers, 6 drugstores, 5 undertakers, 4 employment agencies, and 1 candy maker (Williams).

The number of blacks moving into the district continued to increase with the promise of available industrial jobs. Increased demand for housing in Black Bottom allowed landlords to charge exorbitant rents for units in extreme disrepair. This prompted many tenants to take in boarders, further increasing crowding and the degradation of living conditions in the district.

Towards the end of the decade, black employment in Detroit dropped by almost 30% (Williams). The stock market crash in 1929 only exacerbated the dire circumstances of Black Bottom’s working-class families.

1930s. Following the stock market crash in 1929, the United States entered the Great Depression. Soaring unemployment rates of the 1930s remains unparalleled in American history. President Franklin D. Roosevelt attempted to ameliorate the high unemployment rate and extreme housing conditions of many working class Americans through his New Deal initiatives. For the thousands of blacks living in Black Bottom, this meant the construction of the nation’s first black public housing development: the Brewster housing projects.

Securing a site for the proposed housing development was not a simple process. White Detroiters built political alliances to stop construction of the black development near their neighborhoods. Consequently, an area of Black Bottom near the intersection of Brewster and St. Antoine was cleared for the Brewster homes. Construction of the development put many blacks back to work and gave Black Bottom citizens hope for decent living conditions.

The Brewster projects covered 15 city blocks and were comprised of two- and three-story townhomes. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was present at the groundbreaking, which was a celebratory event for the Black Bottom community. By 1938, 701 units were available to tenants, and 240 additional units were constructed over the next three years (Williams). At its peak, the Brewster Homes were home to 8,000-10,000 residents, including future Motown artists Stevie Wonder and Diana Ross (Williams). Joe Louis also began his boxing career at the Brewster recreation center.

1940s. With the United States’ entry into World War II, blacks were hired to fill job positions while soldiers were away at war. Between 1940 and 1950, black employment rose from 29 to 45% (Williams). This surge in employment brought another wave of black migration to Detroit, which again resulted in a significant housing shortage in Black Bottom. Living conditions continued to decline, and most housing still lacked proper plumbing, electricity, and heat. Even though some black workers could afford to buy homes outside of Black Bottom, racially discriminative housing covenants prevented most from doing so.

The federal government funded the Sojourner Truth housing project to alleviate the existing Black Bottom housing population by diverting black residents into other neighborhoods. The black housing development was controversially built near a predominately white neighborhood. White and black homeowners in the neighboring community were afraid that the density of black tenants would lower their property values. Residents collectively picketed and protested the project and successfully stalled occupancy for months. Eventually, the National Housing Agency officially ordered black tenants to move into the Sojourner Truth homes, and state law enforcement provided security and order for the new residents.

1943. The Detroit Riots. The conflicts surrounding the Sojourner Truth homes foreshadowed the eruption of racial tension in the riots of 1943. On June 20, a fight on Belle Isle escalated into a massive uprising that swept through Detroit. As police and riot squads tried to dissolve the hostile mobs, more than 10,000 Detroiters rioted in Cadillac Square, incited by racism, unemployment, and housing practices (Williams).

Even one month after the riots ended, Black Bottom still bore marks of the insurrection. Residents and business owners continued to repair their homes, businesses, and lives.

1950s. The 1950s in the U.S. are marked by massive urban renewal projects that sought to eradicate the extreme living conditions in American slums. Mayor Jeffries’ 1951 Detroit Plan slated Black Bottom as an area for slum clearance with plans to build I-375 through the district.

By 1951, 140,000 blacks rented and resided in Black Bottom (Williams). Some middle-income black families were able to relocate from Black Bottom to more prominent Detroit neighborhoods. Some low-income blacks moved to Herman Gardens, another black housing project in the city. Without a public relocation program, however, the fate of many historic Black Bottom residents remains unknown.

Black Bottom was completely razed by 1954. Like other urban renewal projects, significant areas of the former Black Bottom neighborhood remained vacant for over half of a decade. The district was nicknamed “Ragweed Acres,” and “Mayor Cobo’s Fields” while it idly waited for a developer (Debanné). Herbert Greenwald, a Chicago developer, eventually collaborated with urban planner Ludwig Hilberseimer, architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and landscape architect Alfred Caldwell to design and develop the site. Construction of Lafayette Park began in 1956.

Sources:

- Debanne, Janine. “Claiming Lafayette Park as Public Housing.” Case : Lafayette Park Detroit. Ed. Charles Waldheim. Harvard University Graduate School of Design, 2004.

- Williams, Jeremy. Detroit: The Black Bottom Community. Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

- Thomas, June Manning. Redevelopment and Race: Planning a Finer City in Postwar Detroit. The John Hopkins University Press, 1997.

- Bak, Richard. Detroit Across Three Centuries. Sleeping Bear Press, 2001.

Images:

- Burton Historical Collection (BHC)

- Walter P. Reuther Library (WRL)

Brief Chronology of Black Bottom. (Download PDF)

Detroit Stories: One Narrative of a Black Bottom Resident. Detroit Stories is a growing, collective voice of an authentic city. This digital archive contains stories that are honest revelations and heartfelt recollections. These are the stories of real people living and working in the City. The methodology is simple. Detroit Stories sets up at various events in the City and interviews volunteers who share their stories in earnest. Authenticity is central to Detroit Stories. The content is real, and all footage is minimally edited to maintain and embrace an aura of authenticity. This intention is a core value of the project. Bernice Jamerson is the first individual to be premiered by Detroit Stories, and Ms. Jamerson truly sets the tone for the project. She is a Detroiter through and through and has seen and experienced much of the City’s evolution over the years. From growing up in Black Bottom to working at the Federal Government’s Tank Arsenal to volunteering as a patient advocate at St. John’s Hospital, Bernice has several stories to tell.

Detroit Stories is a civic engagement initiative within the Detroit Works Long Term Planning process. As stated by Dan Pitera, Co-Director of Civic Engagement for Detroit Works Project Long Term Planning, “Detroit Stories, much like the Detroit Works’ Long Term Planning process, is capturing a growing collective of authentic voices that represent Detroit. It is the stories and experiences of Detroiters that will ultimately help to shape the data and analysis that’s being done to create a new roadmap for the city’s future. The people featured in these films, and the thousands of community members across Detroit they represent, are the reason we are working hard to create a new strategy for Detroit that will improve the quality of life of all who live, work, play and worship here.”

New “Detroit Stories” will be shared every Thursday at DetroitWorksProject.com beginning the 22nd of March, 2012. Each participant shares a series of earnest stories about being a Detroiter. All films will be archived on detroitstoriesproject.com, and further updates and releases will be posted on facebook.com/detroitstories. All films are produced by Spirit of Space (detroitstoriesproject.com) in collaboration with the Detroit Works Project.